Golden Note – May 2018

For a brief time, Brighton was a center of Gold Rush excitement

By Bill George

It’s well known that the first gold strike was at John Sutter’s sawmill on the American River at Coloma. Sutter’s saw mill was built to supply lumber to build a flour mill to help feed the pre-Gold Rush settlers who were coming into California. “I was very much in need of a new sawmill, to get lumber to finish my large flouring mill, of four run of stones, at Brighton,” Sutter wrote, establishing the name of Brighton in California history.

In 1848 Sacramento was located in what is called Old Sacramento today. A road led to Sutter’s Fort, just a little over two miles to the east of the downtown. Another three miles east of the fort was Brighton on a “beautiful” bend in the American River with a 150-foot wide levee. Today you can visit the area by walking across the Guy West Bridge that crosses the American River at Sacramento State University.

To speculators, it seemed the ideal spot to build a suburb so people could escape noisy, dirty and cluttered Sacramento. Brighton was far enough away for peace and quiet but close enough for busy workers to commute to town via an omnibus over an “excellent road.” Or they could avoid the congestion and the wagon trains on the road and sail into town on a small steamboat. Newspaper reports, augmented by intense advertising, promoted the new town of Brighton in glowing prose. “Town Lots for Sale,” proclaimed one ad. “The situation is one which makes it delightful and healthy as a place of residence; No place is more richly enhanced with pure water and refreshing air.”

A reporter for the Sacramento Transcript was given a tour of the town and was duly impressed. “We had the pleasure yesterday of a delightful ride out along the banks of the American River to the site of a new town. It is situated on that locality known as Brighton. The town will be a pleasant resort for the denizens of our city during the few leisure hours they can steal from their business. The land around is fertile and easily irrigated and we expect to see a flourishing little suburban town spring up there before many months.”

The rival Placer Times newspaper also had effusive praise for the plan. “The oaks have put on their full spring dress, and woo the traveller to their refreshing shade. The entire road from the city, 6 miles in length, presents a complete caravan of teams, some with full loads for their various destination, and others returning for fresh cargoes. For healthy and delightful family residences, as well as a temporary resort for recreation, nothing can exceed the attractions of this pleasant little village on the American Fork. It is quite the Harlem of Sacramento.”i In the 1850s Harlem was a rural community known for elegant country living north of crowded Manhattan.

The centerpiece of the new town was a structure called the Pavilion, a hotel operated by John Frink and Curtis Andrews. It was built next to the first oval racetrack in the Sacramento area.ii Looming over the river and the surrounding plain, the Pavilion was a unique and imposing building. Built at a cost of $30,000, it was three stories high, “with a double balcony in front. The bar-room is spacious, and will not only during the races, but at other times, be a popular place of resort for the denizens of our city, who take horse and ride out during our hot days, to catch a little country air. The public parlors and the reading-room are very conveniently arranged on the first floor. On the second floor is a spacious and elegant dining and ballroom, the windows of which reach to the floor, and open out onto the balcony. The second story also contains private parlors for families, and sleeping apartments. The third floor is divided into sleeping apartments of convenient size.” iii The balconies overlooked the river, and a bowling and billiards hall were in the works. The Pavilion had it all.

The Brighton racetrack immediately started drawing large crowds. “Several hundred persons assembled at Brighton yesterday afternoon, to witness a race which had quietly been announced to come off, between a sorrel horse owned at Brighton, and a black mare for $500 a side. The race was for a quarter of a mile. For a little more than the first half of the heat, the mare led about half a length; but when within about a hundred yards of the close, the sorrel let out a little and passed her, coming in at least three lengths ahead. Considerable interest was manifested by the spectators.”

Other “crack nag” races included a match race between “the famous horse Ito” and a bay named Buck Hall, with each side putting up $3,000 to back their steed. Ito’s owner was a man named J.P. Rynders, and he was so confident of Ito’s prowess he issued a challenge “TO THE WORLD” in San Francisco’s Daily Alta California newspaper. He would bet up to $10,000 on his horse “against any horse, mare or gelding” at the Brighton Course. Alas the race never happened, as Rynders wrote cryptically “I hereby withdraw the above challenge.”iv

The track featured “a high, tight board fence entirely surrounding it, with a large grandstand, a judges’ stand, and a number of stables for the accommodation of race horses.” v A trainer was on hand to offer owners assistance in grooming and getting the horses ready to race. The Brighton Jockey Club set a portion of the grandstand aside for ladies and established race times at 2 P.M. daily.

The track pulled in fans of other sports as well. Long distance running became popular in the United States in the 1840s and began drawing large crowds and, of course, intense wagering. The runners were called “pedestrians” and traveled around America challenging all comers for prize money. One of America’s great early long distance runners showed up to train at the Brighton racetrack in 1851. John Gildersleeve, a five-foot-five inch New York fireman, had won fame when he defeated two Englishmen in front of 20,000 fans in New York. The English were considered to be the best runners in the world, but Gildersleeve won two of three races from the Brits, becoming a national hero. Arriving in California, Gildersleeve issued a challenge in a number of newspapers to “any man in California to run a foot race from five miles to almost any distance.” He backed his “opinion of his speed” with a wager of $5,000 on himself. Preparing for his match races, he drew crowds to Brighton to watch him train. The landmark running barrier of the day was running ten miles in under an hour, and Gildersleeve put on quite a show at Brighton, attracting a large crowd and running ten miles in 1:04:22, just missing the mark but creating a lasting memory for running fans.vi

A boxing match between Thompson, “an Englishman” and Willis, a “Vermonter” was held in June of 1852, and attracted a crowd of about 2,500 fans, many of whom were “fancy” with a sprinkling of females and San Franciscans in attendance. Although the fans cheered for the American, they wisely did not wager on him, and Thompson “superior in every respect” won the “very lame affair hardly worth the name of a fight” in nine rounds. Other entertainments at the Brighton track included a battle between a “full sized grizzly and a large bull” before a crowd of 2,000. No report on who won.

While sporting and other entertainments were popular attractions, perhaps the most colorful Independence Day celebration in Sacramento history was held at the Pavilion hotel in 1850, just months before California was granted statehood.

A grand dinner, a fancy ball and fireworks highlighted by salutes from a cannon drew hundreds to town. Headlining the affair was Captain John Sutter himself, resplendent in his blue uniform with gold epaulets, surrounded by a group of exiled Hungarian officers and Prince Paul Wilhelm of Wurttemberg, one of the wealthiest men in Europe. They must have overshadowed Mayor Hardin Bigelow, Governor Peter Burnett and General A.M. Winn and the roughly clad 49ers, but not the “beautiful array of the fairer sex” that swirled around the ballroom floor.

With the liquor flowing, a series of toasts were proposed, each accompanied with a strong drink and a blast from a cannon. A damper was put on the event when the man firing the cannon suffered a broken arm and burnt face when the gun went off unexpectedly. Things got a little rowdy after the party when two or three drunken scuffles broke out, but only minor injuries resulted. It was all “settled on the most amicable basis” and the reporter covering the party noted that no “affair of honor” (a duel) would result from the “little incidents.”

Despite the misfired cannon and the drunken brawls at the Pavilion everyone went home alive. The same could not be said of the next big event in Brighton, which was rapidly approaching.vii

On August 15, 1850 a violent dispute over land tittles erupted in a shoot out in Sacramento that would become known as the Squatters Riot. The mayor was wounded badly and the city assessor killed, as well as a number of squatters.

The next day Sheriff Joseph McKinney, armed with arrest warrants gathered a posse of some twenty men and rode out of town to begin searching for a squatter named James Allen. The sheriff was told the man he wanted was in Brighton. The posse galloped past the Pavilion and found Allen’s house nearby, with Allen and a number of squatters armed and waiting. Calling out for Allen and his companions to surrender, the sheriff walked into the house, and gunfire erupted. The sheriff was shot, stumbled out the front door, collapsed and died. Allen’s brother was shot and killed in the melee, and others on both sides wounded. The posse prevailed, taking the surviving squatters prisoner, but Allen, wounded badly, somehow managed to escape.

The Pavilion became a temporary headquarters and place to hold the prisoners, who were returned to Sacramento. The episode ended in just a few intense hours. Allen was never arrested. He fled to Hangtown, modern day Placerville then to Missouri where he had previously lived. Years later it was reported he was living in Brighton again. He was never arrested for his actions in the shooting of Sheriff McKinney.

Life in Brighton quickly returned to normal, with races at the track and events at the Pavilion.viii

John Frink, one of the Pavilion owners died, and on April 26, 1851, and the Pavilion was auctioned off by the businessman and banker Barton Lee to satisfy a debt of $9,566.ix In June of 1852, it was announced the Pavilion had changed hands and was offered for rent. Meanwhile, it was under the control of a Col. Kipp, who promised to keep the “the bar open with the very best of wines, liquors and cigars.”

In mid-October 1852 the Pavilion met that tragic fate so often encountered in the 1800s, destruction by fire. The Sacramento Union carried the sad tale; “We regret to learn that the large and beautiful hotel known as the Pavilion, together with the stables, outhouses and fences surrounding it, were totally destroyed by fire yesterday afternoon. It was one of the handsomest and most commodious hotels in this section of the state.”

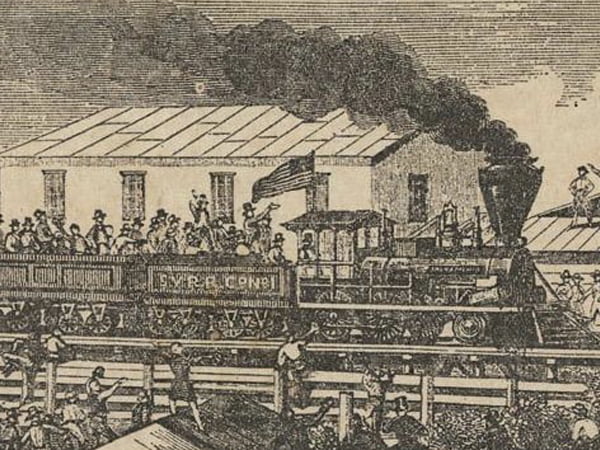

Snuggled next to the river, Brighton was often inundated during the floods of the 1850s and 60s. The town site was abandoned and reconjured south of Folsom Boulevard near where the Light Rail tracks are located today. It served as a remount station for the Pony Express, and the Sacramento Valley Railroad stopped nearby.

One structure that harkens to Brighton’s beginning is the former Brighton School, now the Edward Kelly School, still in use today, as a pre-school. It is the oldest continuously operating schoolhouse in Sacramento County. In 1924 the school was moved from Brighton and you can find it at Bradshaw Road at Lincoln Village Drive.

Like the Gold Rush itself, Brighton flourished briefly, violently and yes, brightly and then was gone. The American River still courses through the bend and you can see why this spot was chosen as the site for a palace hotel and a lush green racetrack. The races and boxing matches that drew thousands of cheering fans faded as quickly as the excitement of the Gold Rush.

Fond thoughts of Brighton must have lingered in the mind of Charles Pettit, a Brighton pioneer who wrote a reminisce of the Pavilion and the race track some forty years later in the Sacramento Union in 1892. “In speaking of early-day race horses,” he admonished modern readers, “we must not forget to mention Wake-Up-Jake and The Boston Colt.” Or, I would hope, the great “pedestrian” runner Gildersleeve.

Bill George is publications chair of the SCHS. He produced a number of documentary films on early California history after a career in television news and public relations. He worked at KCRA-TV , Sacramento from 1982-1987.

_____________________________________

i Placer Times, Oct.13, 1849.

ii Sacramento Transcript, July 2, 1850.

iii IBID.

iv Daily Alta California, August 16, 1851.

v Sacramento Daily Union, August 8, 1892. This is from Charles Pettit, recalling events some 40 years after they occurred. At first the author was skeptical of Mr. Pettit’s recall, but found them confirmed in other sources.

vi Sacramento Daily Union, September 29, 1851. Also see Daily Alta California, October 22, 1851. For a history of mid-1850s runners, see Dale A. Somers, The Rise of Sports in New Orleans: 1850-1900. There are several references to Gildersleeve in the papers of the 1850s, and his name was used as a synonym for speed. In December of 1851 it was reporter he was opening an oyster saloon in Marysville.

vii The primary source for the wild Independence Day celebration is the Sacramento Transcript, July 6, 1850. For more on Prince Paul’s experience, see Albert Hurtado, John Sutter, a Life on the American Frontier, pg. 281-285.

viii The primary source for the Squatters Riot is the August, 1850 editions of the Sacramento Transcript. Also Mark. A. Eifler, Gold Rush Capitalists, Chapter Six, Dangerous Ground.

ix Sacramento Transcript, April 29, 1851

x Brighton School, Wikipedia.